How J.Jill's IPO Could Help Define E-Commerce Valuations

You’d be forgiven for missing a small cap retail IPO last week in the midst of the global Snapchat mania. Last Thursday, without much fanfare, J.Jill, a nearly sixty year old former mail order catalog company selling women’s apparel, quietly went public at a nearly $900M enterprise value. And surprisingly, for the complex world of digital commerce, J.Jill’s public market reception might actually be an indicator of what all these next gen direct-to-consumer commerce businesses are actually worth.

In past pieces for BreakingVC during 2016, I’ve discussed Amazon’s impact on both e-commerce and retail at length, as well as the three areas I’ve observed for opportunity to penetrate Amazon’s digital commerce force-field: (1+2) In Why Amazon Has Consumer Investors Bemused and Confused I wrote at length about both off-price retail (Marshalls and T.J. Maxx, for example) as well as mid to upper tier brand opportunities that Amazon fundamentally can’t capture and (3) in The Middleman Strikes Back, I described how Amazon’s anemic commerce margins prohibit it from a service heavy assisted/concierge-commerce provider.

But for everyone else – from Warby Parker to Harry’s to Bonobos to Everlane – what are these weird, sorta digital, sorta omni-channel, sorta personalization brands actually worth? And why is a sixty year old women’s apparel business that was previously spun out of a legacy retailer, Talbots, a leading indicator of value?

As usual, the Company’s S1 is a store of insight and surprises:

Personalization and Loyal Customers

If I were reading an untitled prospectus, I would’ve bet my money that the following block of text from the Company’s S1 “Overview” described a millennial-first next gen commerce brand, with a small but growing retail footprint:

We believe we have strong customer and transaction data capabilities, but it is our use of the data that distinguishes us from our competitors. We have developed industry-leading data capture capabilities that allow us to match approximately 97% of transactions to an identifiable customer, which we believe is significantly ahead of the industry standard. We maintain an extensive customer database that tracks customer details from personal identifiers and demographic overlay (e.g. name, address, age, household income) and transaction history (e.g. orders, returns, order value.) We continually leverage this database and apply our insights to operate our business as well as to acquire new customers and then create, build and maintain a relationship with each customer to drive optimum value.

Believe it or not, that is a sixty year old company talking.

The truth is that most retail businesses are really merchandising and logistics businesses more than personalization businesses. Most big box retailers – or at least the many that I speak with – admit that closing the loop between online-to-offline transactions is amongst their largest struggles.

This is a flaw that digital first businesses – even those with a retail footprint – claim they can solve. And all the moreso, a business such as Stitchfix, which is truly a data business at its core, led by Eric Colson, Chief Algorithms Officer. Case in point, a recent Stitchfix blog entitled “Ruminations on Data Driven Fashion Design,” which noted:

For example, can statistical modeling identify when a successful blouse has an attribute that is holding it back? If so, can we suggest a mutation that replaces the underperforming attribute? To illustrate, can we identify when a parent blouse is successful despite its leopard print, and then change it to the floral print that everyone loves this season? We are also examining how we can leverage less structured types of data. For example, can we extract features from images of blouses or the text feedback that clients provide in response to a blouse?

[To be blown away, visit the Stitchfix Algorithms Tour, built by Colson. It is a wow.]

Data is powerful. But it’s goal is to yield a more engaged customer; in J.Jill’s case existing active customers [within the past five years] represent 70% of annual revenues – an awfully consistent customer who sounds pretty darn comparable to all those subscription commerce businesses that have proliferated the market. And very similar to the vision today’s D2C brands are claiming: own a customer’s wardrobe/apparel/bathroom/etc with a non-commoditizing product and they will come back to you year after year.

J.Jill also looks a lot more like a direct to consumer business than your traditional retailer, with 42% of 2016 sales (growing to 50% in 2017) coming from direct channels.

What about its retail footprint? As discussed in the past, many of the next gen millennial brands are launching brick and mortar stores to prove a new customer acquisition channel against an overly saturated (and unprofitable) digital marketing environment. But with a footprint of only 275 retail stores, its brick and mortar presence is at least relatively comparable to the type of presence today’s next gen retailers are aiming for (as of today Warby has 44 B&M locations, Bonobos has 11, etc.) And these stores, like the millennial brands are conceptually customer acquisition drivers, as the S1 notes: “While 64% of new to brand customers first engage with J.Jill through our retail stores, we have a strong track record of migrating customers from a single-channel customer to a more valuable, omni-channel customer.”

At the end of the day, J.Jill, this under the radar retailer looks surprisingly similar to today’s D2C commerce businesses:

Data-first approach (97% of transactions properly attributed to customer profile)

Heavy direct sales focus, with stores used merely as customer acqusion tool (42%, growing to 50%).

Not overbearing retail footprint

Brand quality margins (65.9% gross margins), as compared to 42% for Macy’s, 35% for Nordstrom or 40% for Gap – effectively double the margin basis as a traditional retailer.

What’s It Worth

I like J.Jill as a comp for many of today’s e-commerce companies for two reasons. First, as proven in the prior section, I think it looks much more similar than a casual observer might guess to those businesses. But secondly, at ~$500M in annual revenues, J.Jill is surprisingly small for a public retailer. Gap posted nearly $16B in revenue in 2015, Williams Sonoma is on the small side with $4B in revenues – even Lululemon has trailing revenues greater than $2B. This looks similar to emerging commerce brands which are typically much smaller than their relative press coverage would imply: Dollar Shave Club was on a $250M revenue run rate when acquired by Unilever, Warby Parker booked an estimated ~$200M revenue in 2016, and Trunk Club was on a reported $100M revenue run rate when acquired by Nordstrom. Most of today’s emerging brands, even at triple their current size, would look substantially similar to a small cap IPO.

The first piece of very good news for emerging brands is that there was a market appetite for a small cap offering of this nature whatsoever. Although the Company ultimately priced at $13/share, just below its suggested range of $14-16/share, the good news – again – is that market interest was strong enough not to justify pulling the offering entirely.

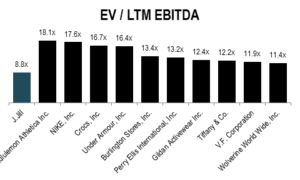

But that’s mostly where the good news stops. J.Jill’s IPO (even based on an estimated $15/share offering) would have it placed towards the bottom of a peer set on a valuation basis. The following graphs on valuation comps were initially published on Seeking Alpha:

Those are sobering multiples (and, the company actually priced 10% below these estimated multiples) for a company that stacks up extremely well on most operational metrics – for example, they boast higher product gross margin that brands such as Tiffany’s, Michael Kors, Ralph Lauren or even Abercrombie. They boast a higher direct to consumer sales percentage than most of their peers. They have an exceedingly loyal customer.

The biggest knock on the company is their growth rate: 10-15%/year – and one of their biggest divergences against today’s emerging brands who are mostly growing at 50-200% annually.

Given these multiples, e-commerce brands need to bank on the following two factors to earn a premium valuation in the market: maintain strong growth rates and maintain high visibility, momentum brands. J.Jill is a fundamentally strong company – and it has stolen much of the playbook from the online brands – but it lacks both velocity of growth nor excitement around its brand proposition.