Anatomy of a Managed Marketplace

The following article was originally published on Techcrunch on May 25, 2017.

Managed marketplaces (also known as end-to-end or full-stack marketplaces) have been one of the hottest categories of venture investment over the past several years. Recent examples of high-flying managed marketplaces include The RealReal, Opendoor, Beepi, Luxe and thredUP, which have collectively raised nearly a billion dollars. They garner a lot of press because the consumer experiences are often radically different than what’s previously been available in the market.

But there is confusion over what a true “managed” marketplace is. It’s fairly easy to spot a true managed marketplace if you know what you’re looking for. Managed marketplaces typically adhere to the following characteristics:

A value-added intermediary (the “management” or “service”) that provides a superior experience versus more traditional peer-to-peer marketplaces, brick and mortar or even a legacy service provider.

An introduction of additional risk into the business model; examples might include pre-purchasing and holding inventory or via investing in services related to the buyer/seller that are an incremental, variable cost before any profits have been realized (money goes out before it comes in).

A take-rate (gross margin) that is a significant premium versus other buy/sell options in the market in order to offset the premium service level or risk transfer that has occurred.

It’s important to note that many of today’s ubiquitous marketplace companies such as Uber, Airbnb, Grubhub and others are “lightly” managed, by which I mean they invest resources in quality assurance, background checks and verifying reviews. But these services are typically a de minimis expense on the company’s overall operating cost structure — often even considered as part of the customer (or merchant) acquisition cost — and therefore do not classify as a fully managed service.

For Airbnb, these “light” costs might include the costs related to verifying a user’s home address, or the customer service costs of resolving disputes. For Grubhub, the light management might include the costs related to updating menus, but they are not fully managed in that they are not taking ownership of the food or food prep themselves (although Grubhub has begun rolling out delivery, which would qualify as a managed service). This infographic shows the primary marketplace categorizations:

In order to build a successful, sustainable managed marketplace, the take-rate margins must be high enough to support that value-added intermediary and the subsequent amount of services and risk the marketplace is providing. What makes these marketplaces so powerful is that they can drop a comparable amount of contribution margin to the bottom line while investing the higher take-rate revenues into customer experience, reducing friction and product improvements.

Additionally, if, over time, these marketplaces can develop technology that significantly reduces or eliminates the costs of providing these value-added managed services, they can continue to justify higher take-rates and build high-margin businesses that are worth a premium to their traditional service provider comparables or peer-to-peer businesses.

As a primer, here’s a quick chart of take-rates in the re-commerce industry amongst both managed marketplaces and traditional marketplaces. Can you guess which ones are actively managed?

Value innovation and risk

Now that we’ve identified that managed marketplaces are effectively business model innovations, it’s useful to go through a few on a case by case basis to identify each of these innovations and be able to properly identify managed marketplaces in the future.

Opendoor is a managed marketplace in the real estate industry that is an on-demand tool for selling your home. They utilize numerous data sources to offer real-time bids on a home, typically without ever stepping foot in it. Basically: Click a mouse, sell a house. They charge the typical 6 percent brokerage commission plus a risk-adjusted service fee (about 2-3 percent extra, on average, up to 6 percent).

Value-Add Innovation: A consumer no longer has to wait to sell their home. They don’t even so much as have to engage a real estate brokerage. Opendoor reduces the friction of selling a house from possibly months (and multiple showings) down to minutes. The company will also perform all maintenance/changes demanded by a licensed inspector.

Risk Innovation: Unlike brokerages such as RE/MAX or Century 21, which take zero capital risk on a transaction but collect 3 percent from each of the buy/sell sides of a transaction, Opendoor is buying inventory and holding it on their books. The effect of this is that they can offer an extraordinarily differentiated experience to their home sellers, who traditionally rely on peer-to-peer markets (typical MLS listings, with a realtor advising).

Take-Rate: To justify this level of risk (holding inventory) and service (managing maintenance), Opendoor charges a take-rate on average 50 percent higher than in a traditional real estate transaction. While a 50 percent premium may seem marginal given the delta in other categories, the large transaction sizes in real estate mean that the take-rate premium on a $500,000 house is $15,000 of incremental gross margin. That is a significant amount of money to manage maintenance and some risk.

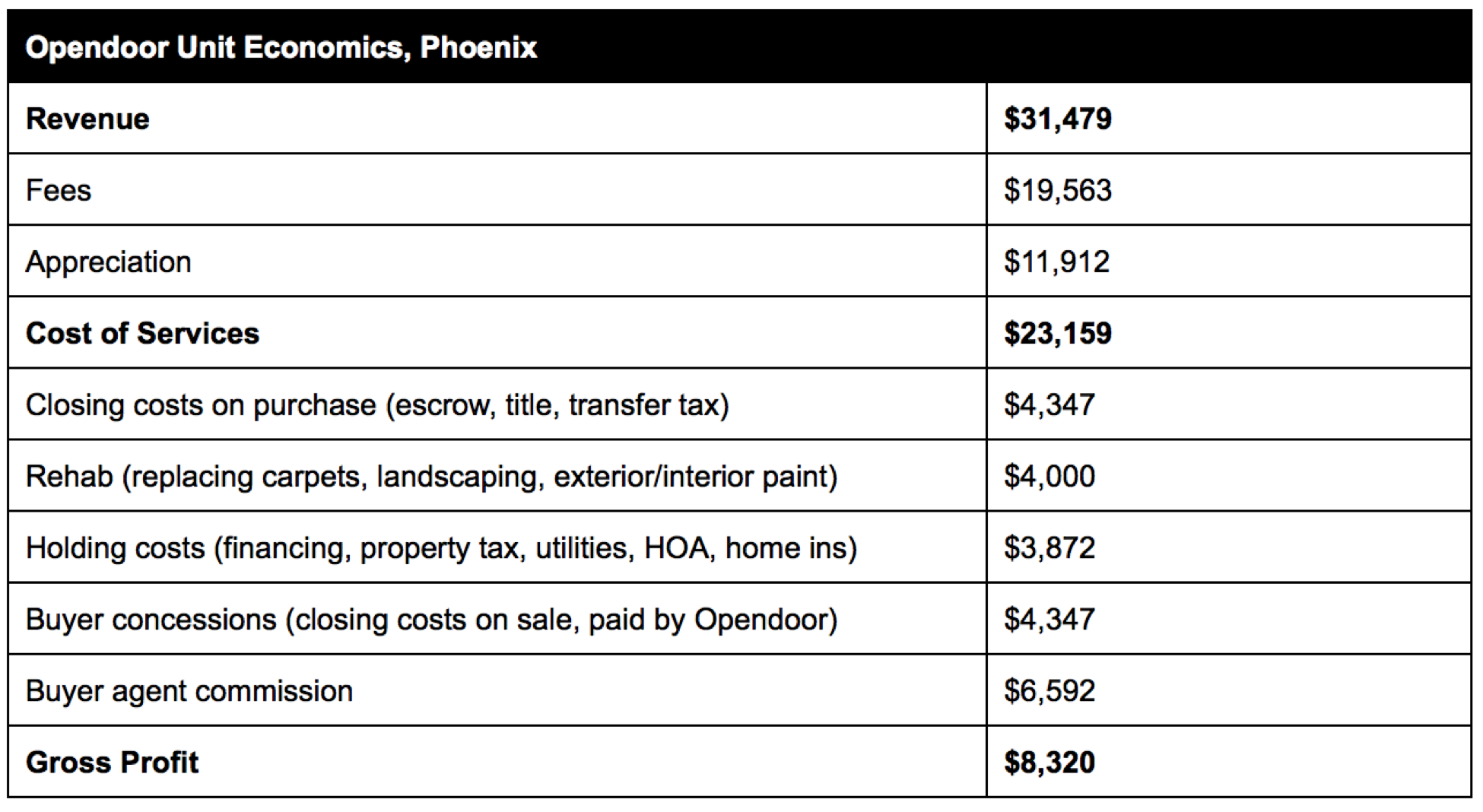

Case in point is the below estimation of Opendoor’s revenue and cost structure on an average $220,000 home (their sweet spot) with a 9 percent brokerage fee, a 50 percent premium to market rates:

Source: Inside Opendoor: What 2 Years of Transactions Tell Us

For Opendoor, when all is said and done, their average net profit, $8,320, or 3.8 percent of the home’s original selling price, is still greater than the 3 percent an agent at a traditional brokerage earns. And, they are able to provide a substantially differentiated experience. It’s a powerful model.

TheRealReal is a managed marketplace in the luxury consignment space focused on clothing, jewelry, handbags, even art. The experience differs from eBay, for example, in that sellers need to provide zero effort other than sending their goods to a TRR warehouse (no photography, no descriptions, no customer interaction) and buyers take comfort in TheRealReal’s quality and authentication services, which they fully guarantee.

Value-Add Innovation: Rather than having to post online listings and photographs of items, pay for a third-party authentication or even deal with shipping, TheRealReal simply collects an item from a consignor and sends them a check once it sells. For sellers, it’s a true “set it and forget it” experience and is multiples more convenient than dealing with online auctions (or even price comparing between local thrift shops).

Risk Innovation: In order to provide a frictionless experience for the seller and an aesthetic, trusted experience for the buyer, TheRealReal is forced to frontload all those costs into their own overhead. They expense per-item charges for photography, copy writing and logistics before an item sells. If the item fails to sell, TheRealReal is forced to eat those overhead costs. Therefore, if they inaccurately forecast demand for certain items, they could end up burning more money than they’re able to recoup on sales.

Take-Rate: In order to justify its cost structure, TheRealReal (and other comparable marketplaces) command take-rates of 30 percent, effectively triple what non-managed, peer-to-peer marketplaces charge as a commission to sellers.

Luxe is a managed marketplace for drivers that reduces all friction associated with parking: finding a lot, searching for a spot, returning to the lot, paying the cashier and waiting to exit. Operating as an effective always-on, mobile valet service, drivers are met at their destination by a Luxe agent who takes the keys and parks a driver’s car. Upon leaving, the driver requests their car in-app and are met by a Luxe agent who delivers their car at their exit point.

Value-Add Innovation: Luxe fundamentally reimagines parking by providing any driver with an on-demand valet who will meet them across a large radius of major cities. Unlike traditional parking or even mobile parking marketplaces such as SpotHero* (which require a driver to park their own cars), Luxe reimagines driving to be destination-focused: drive to your ultimate end-point, not a parking lot. In theory, its product could save drivers time and enable them to avoid inclement weather.

Risk Innovation: In order to provide uninterrupted, on-demand service, Luxe is forced to employ numerous valets across each geography in which it operates. Irrespective of what these valets are actually paid, it is a considerable human capital cost that Luxe is forced to bear ahead of any realized demand. This is in contradistinction to a sharing economy marketplace model such as Airbnb or Uber who are not burdened with human capital costs, but rather pay transactional commissions on any given home-owner or driver.

Take-Rate: In order to counter-act the considerable human capital expense of staffing valets across a city, Luxe should be forced to charge a material premium compared to average hourly parking rates in a particular city. It is therefore quite surprising that they advertise an average of $5/hour for their service, especially when the average hourly rate in NYC, for instance, is $11-15/hour. Several months ago, reports from San Francisco suggested that prior rates of $5/hour have now increased to $15/hour or a $45 daily maximum and, as of this month, they have suspended the valet service. Given the considerable variance in parking costs by neighborhood, it is hard to assess their exact take-rate premium, but I’d estimate it would have had to have been about 200 percent of traditional parking take-rates to be profitable.

Each of these companies is built on the vision that technology will ultimately be able to deliver increased automation and better margins. For example, that one day TheRealReal’s item authentication will be entirely algorithmic or that Luxe will be able to predict the real-time flow of drivers, thereby reducing its human capital costs. Because these representative companies are all still relatively young startups, those tech-driven narratives have mostly only begun to play out.

Beepi versus Carmax

Beepi, a managed marketplace for used cars, recently closed its doors after burning through nearly $300 million in the span of two years. Unlike eBay Motors, which is a peer-to-peer experience, offering no concierge services (although it does offer some self-service options such as free Carfax reports), Beepi was a full-service platform promising rigorous inspections on cars, a 10-day no-questions return policy for a purchased car and, for sellers, a promise that if one’s car didn’t sell in 30 days, Beepi would buy it outright for the appraised value.

The seller fees for this risk-free service? Approximately 9 percent with Beepi… versus a $125 fee for eBay motors, or about 1.25 percent on a $10,000 car, nearly an 800 percent differential.

So with a premium 9 percent take-rate, how did Beepi fail?

The best insight into their failure may come from a similar model with considerable success. It turns out that the nation’s largest retailer of used cars is also arguably one of the most recognized managed marketplaces in the world: Carmax. Give Carmax 30 minutes to inspect your car and they will buy it, even if you’re not purchasing one of theirs, with a “no-haggle,” take it or leave it offer. Thirty minutes is pretty efficient, pretty darn close to on demand.

The extraordinary thing about Carmax is that the Company’s gross profit per used car sold basically doesn’t change even when the year’s average price per car sold moves up or down by 5 percent in any given year. Which means that Carmax is actually less focused on their take-rate per car, but instead focused on their profit per car; their commission is a function of the profit they expect to earn.

Rationally, this makes sense as well — consumers value convenience but have a cognitive dollar limit they are willing to trade for that convenience. By inverting their take-rate to be a function of their profit expectations, Carmax is able to offer more for higher-end cars where a 10 percent difference between the car’s BlueBook value and Carmax’s offer would likely be too extreme for a customer to accept. For high-priced assets, a flat tax is fundamentally unlikely to work.

Used cars are curious assets in that they depreciate so quickly that even 60 days can have a demonstrable impact on value. This is where Carmax excels. In their most recent annual reporting, Carmax notes having sold more than 600,000 cars in the prior year with (then) present inventories at about 55,000. That’s a retail turn of about 11, meaning that a car moves off Carmax’s lot every 35 days or so, allowing them to more accurately price cars andmake higher offers, being less exposed to the less predictable volatility of depreciation.

In a post-mortem on Beepi, Carlypso founder Chris Coleman suggests that in addition to the noted reasons (depreciation effects, and cognitive pricing differential), the approach was inherently flawed from a customer acquisition perspective. Specifically, that while there are customers looking to simply sell their car for cash, most car owners are looking to trade-in a car, because they still need a car and there are tax benefits to doing so; a platform that has to pay marketing costs for both the buyer and seller in all transactions is at a significant disadvantage.

At the end of the day, a managed marketplace model for used cars does work. Carmax is only one of thousands of proof points: tens of thousands of dealerships across the country hold inventory, inspect cars and reap a profit. Beepi’s failings appear to be the result of poor execution, mispricings and maybe even some bad luck around a financing that fell through.

Automation and Shutterstock

Because managed marketplaces involve a heavy “service” component to improve the overall experience, one of the expectations of the sector is that as artificial intelligence and automation continue to evolve, the human capital cost of providing the service will decrease if software can assume more of those responsibilities.

But an area of struggle with managed marketplaces is that very few digital managed marketplaces are actually public companies, reducing the visibility into their overall economics and processes — and making it hard to test the assumption that service costs should come down over time. Luckily, there’s at least one: Shutterstock (NYSE: SSTK), a marketplace for photographers to sell their images, bills itself as a “trusted, actively managed marketplace,” in that “each image is individually examined by [their] team of trained reviewers.”

On the spectrum of managed marketplaces, Shutterstock is undoubtedly on the lighter end — with the financial risk from its active management being only the human capital cost of its QA reviewers. Nevertheless, it would seem like this hypothesis is an ideal one to test on a company such as Shutterstock, which isn’t dependent on an unproven technology such as self-driving cars to reduce their cost of providing a service, but could presumably leverage proven, inexpensive image recognition technologies to do much of the quality assurance, copyright detection and tagging that the human reviewers do.

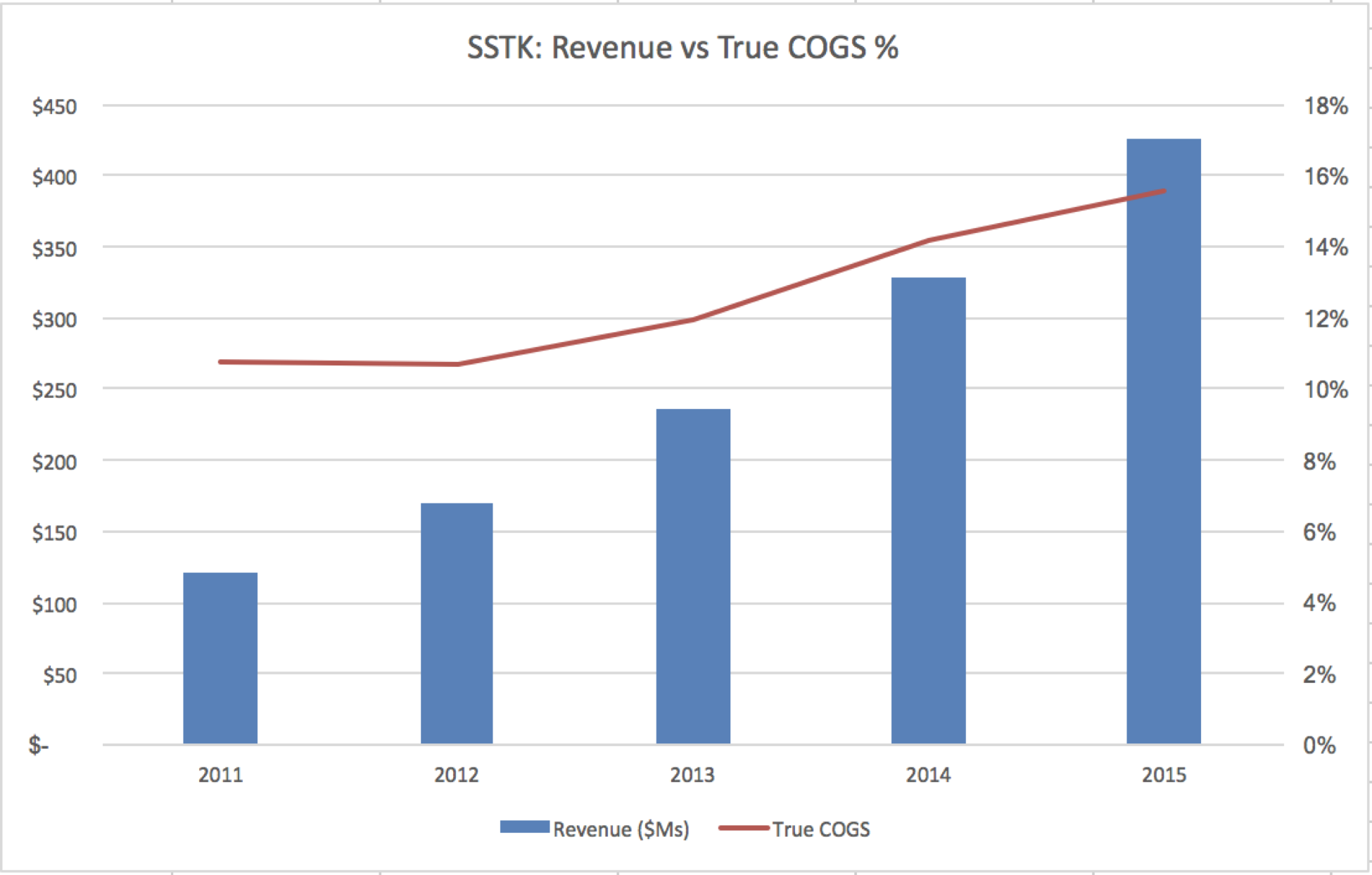

Yet, that doesn’t appear to be borne out by Shutterstock’s financials. To test the automation hypothesis, I decided to look at the company’s revenue versus the cost to generate that revenue. Shutterstock defines their costs of revenue as “royalties paid to contributors, credit card processing fees, content review costs, customer service expenses, infrastructure and hosting costs…and associated employee compensation.” I would assume that credit card processing fees as a percentage of revenue are relatively flat (if not slightly reduced year over year) and that cloud-hosting fees also scale mostly proportionately to demand (revenue). I’ve defined “True COGS” below as the aforementioned expenses to providing their service, minus the contributor royalties:

Surprisingly, rather than decreasing over time, these True COG costs appear to be increasing. Meaning that the same picture that used to take 10.5 percent of revenues to process now costs nearly 15 percent.

There are a number of possible explanations here. It’s certainly possible that these increased costs are because the company is investing heavily into automation, the effects of which simply haven’t been borne out yet while they streamline their QA process. It’s also possible that the number of photos the company maintains makes it more expensive to process each incremental picture — for any variety of reasons.

The learning from this Shutterstock case study, a company which is now 14 years old, is that it’s improper to simply assume that the substantial service-related costs that managed marketplaces incur in their early stages will decrease with “scale,” either through execution or software automation. As with any company, there is always room for improvement, but the above analysis of Shutterstock would imply that it’s nowhere near as easy as flipping a switch.

Takeaways

Managed marketplaces are a quintessential venture investment, allowing entrepreneurs to recast consumer experiences while leveraging venture capital subsidies to hold much of the risk inherent in these managed models.

From a unit economic perspective, the potential automation of much of the service labor that goes into these platforms could be significant. Investors and operators need to remain sensitive that it is ultimately the technology, not heavy services, that will long-term cultivate highly desired business models and margins. But, that future automation could also lower the barriers and defensibility of these companies, allowing peer-to-peer players to launch a comparable offering with similar software.

In my mind, the sustaining managed marketplaces will not only re-imagine the experience they’re approaching, but be focused from the outset on building a data moat around their product, thereby ensuring that they remain the platform of choice, even if software innovation begins to level the overall playing field.

Special thanks to Josh Breinlinger and Rebecca Kaden for their feedback on this article.

*Chicago Ventures is an investor in SpotHero.